Oscar Wilde could easily have been referring to the Cannes Film Festival when he said, ‘Life imitates Art far more than Art imitates Life.’ Everything here looks and feels like a movie. Everywhere you turn there’s artifice. The red carpet is professionally lit, the extras (crowds) are lined up waiting for ‘action’ and the enormous crew (festival staff) could rival any major studio production.

Projecting its own obsession with materiality back into its auditoriums, the 66th Cannes International Film Festival is chiefly concerned with artifice. This year’s official selection also featured narrative structures driven by familial and social concerns. Beginning with the most bombastic, here are 2013’s top ten trends at Cannes:

1. ‘Flossing’

Cannes is bursting with high fashion, rich food and overflowing champagne. Life on the Croisette is so sparkly you need sunglasses to dull the glare of too much bling. Showing off high value goods like this is what’s known as ‘flossing’ (not to be confused with something you do daily to prevent gum disease), and it was present both on and off the screen.

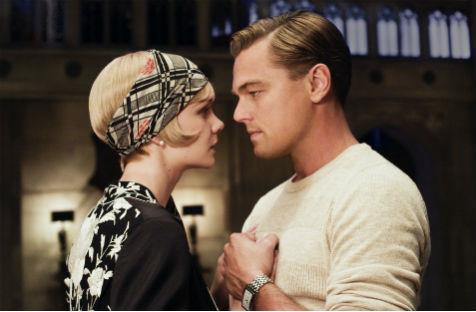

Baz Luhrmann’s long anticipated re-imagining of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s famous The Great Gatsby opened the festival with a gaudy spectacle of 3D, CGI, extravagant set design and bejewelled costumes. Flossing for love, Jay Gatsby tries to win back the beguiling Daisy Buchanan by embodying the American Dream. Unfortunately building love out of affluence isn’t so impressive.

Steven Soderbergh continued the theme with his HBO telemovie in competition, Behind the Candelabra. Another desperate tale of trying to buy love with stupendous opulence, Liberace (Michael Douglas) goes to the ultimate limit asking his partner and chauffeur, Scott Thorson (Matt Damon), to undergo plastic surgery for him From expensive furs to solid gold chains, Liberace turns Scott into another of his expensive objects.

Sofia Coppola’s The Bling Ring examines the shallow attempts of five LA teenagers who repeatedly robbed high profile celebrities including Lindsay Lohan and Paris Hilton in a desperate effort to get one step closer to owning a slice of celebrity pie. But owning it still wasn’t enough. Taking pictures of themselves with the stolen goods the kids would post pictures on Facebook to floss for their friends.

2. Violence

The second kind of excess seen at Cannes this year was violence. Resulting in a number of angry but bloodless walkouts, at least three of the four most violent films used it for social commentary. Jia Zhangke’s Tian Zhu Ding (A Tough of Sin) takes four true crimes stories as departure points for its damning examination of social issues in contemporary China.

Takashi Miike’s Wara no Tate (Shield of Straw) sees a man accused of raping and murdering young girls protected by the law when attempts are made on his life. Concerned with ethics and moral judgement, Miike’s film highlights how violence begets violence.

Amat Escalante’s Heli shows an explicit form of torture against a boy whose desperation to escape poverty and depravity set in motion the causal chain leading to his death.

The fourth, and most extreme example of violence is Nicholas Winding Refn’s Only God Forgives. Winding-Refn (Drive, 2011) has no such commentary to make. All style and no substance, Only God Forgives is as gory as Hostel (2005) but with aesthetic delusions of Lynchian grandeur.

3. The Right Fight

Justice is worth fighting for but not every fight is just. Stephen Frears’ docu-drama, Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight blends stock footage of Ali with a dramatic reimagining of the Supreme Court’s rulings on his refusal to fight the war in Vietnam. Outside of the ring, Ali was only ever interested fighting the system and oppression.

Questions surrounding motivation and conscience are also key in Arnaud des Pallieres’ Michael Kohlhaas, the story of a man who takes the law into his own hands after its processes fail him.

These concerns are echoed in Rithy Panh’s L’Image Manquante (The Missing Picture). Once again using stock footage, along with hand crafted clay figurines; Panh revisits the official history of Pol Pots’ fascist regime, meditating over the people’s fight for revolution.

Adolofo Alix Jr’s Death March uses one specific example from history to question the very nature of human warfare and the individual’s role within it.

4. Children

Mark Cousins (The Story of Film: An Odyssey, 2011) premiered his newest visual essay, The Story of Children and Film, in the Cannes Classic program. Staking a claim for the playful and poignant relationship between children and film, Cousins’ looks at a broad body of works that showcase shyness and performance from children captured on camera. Beautifully echoing Cousins’ sentiments were new films from Hirokazu Kore-eda, Soshite Chichi Ni Naru (Like Father, Like Son), and Asghar Farhadi, Le Passé.

5. Fathers

In the 1960s when film theory was a burgeoning study, psychoanalysis was one of the most useful tools for unpacking the subtext of cinema. In a ‘return of the repressed’ style comeback, this year’s selection had a number of titles that ought to come with a free Freud reader. The examination of the male role model was most prevalent in Kore-eda’s Like Father like Son, Arnaud des Pallieres’ Michael Kohlhaas and Alexander Payne’s Nebraska.

6. Police

The examination of the role of the father extended to the role of societal patriarch: the police force. Questioning here the motives of those in power, Miike’s Shield of Straw reveals widespread institutionalised corruption while Guillaume Canet’s Blood Ties blends the public and private role of the patriarch together, highlighting the difficulty of being able to separate moral judgements from duty.

7. Sex work

An uncomfortable recurring theme this year was the unsavoury connection between representations of cruel masculinity and exploitative sex work. Claire Denis’ Les Salauds (Bastards) deals with an underage girl being forced into sex work by the father figures in her life. Only God Forgives punishes sex workers as well as those who condone sex workers, especially negligent fathers. Most powerful of all though is James Gray’s moving story about the role of desperation in sacrifice of the self in The Immigrant.

8. Weak Women

Aside from Chloe Robichaud’s Sarah Prefere la Course (Sarah Prefers to Run), the majority of female lead characters this year have been disappointingly whiny or dependent on men. Vanessa (Zoe Saldana), Monica (Marion Cotillard) and Natalie (Mila Kunis) can’t do anything without a man stepping in to help in Blood Ties. Crystal (Kristin Scott Thomas) acts tough but when it comes down to it, can’t do the dirty work herself, in Only God Forgives. Ewa (Cotillard in The Immigrant) is alternately dependent upon Bruno (Joaquin Phoenix) and Orlando (Jeremy Renner).

9. Literary Adaptations

Along with this year’s festival opener, The Great Gatsby, James Franco split himself in front of and behind the camera in his split screen reimagining of William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying. Michael Kohlhaas is adapted from the 1811 novella by Heinrich von Kleist telling the story of 16th century Hans Kohlhase. The story is credited as having inspired Kafka to write.

10. Umbrellas

At least half the time here at Cannes has been stood standing in the rain trying to avoid being hit by the many pointy edges of umbrellas. Life imitating art again, this year’s most stunning Cannes Classic restoration was a 2K presentation of Jacques Demy’s Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (The Umbrellas of Cherbourg), an enchanting musical starring a young Catherine Deneuve.

Reinstating the patriarch, re-defining the family in its wake, taking source material beyond its written limitations and ending in excess, the 66th International Cannes Film Festival has set a dark yet fascinating tone for the next cinematic year.