As Egypt continues to struggle at the hands of the conservative Muslim Brotherhood, the results of this struggle continue to be clearly dictated through the art of the country. One example is Marwa Adel, whose photographs represent the growing repression of women and who was recently scolded at her own exhibition by a member of the Brotherhood.

‘He had a long beard and he stood up and told me, “How could you do something like this? You are a Muslim.” He said women should be veiled and covered. His kind wants us to cover our minds, our issues. I told him, ‘Don’t worry about me. I know my God very well,’ she told The Los Angeles Times.

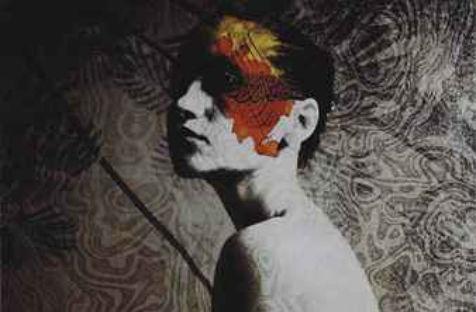

Adel isn’t the only one exploring the issues her country faces through art. Many female artists have also taken to portraying the Muslim veil as a symbol of oppression such as Nadine Hammam, whose exhibition Tank Girl was held in a Cairo gallery last March. Yet there are always those with a different perspective. Egyptian photographer Laura El-Tantawy has taken the opposing view, using her work to challenge the idea that the veil has to be seen as a symbol of oppression and patriarchy.

‘All the way from India to the Middle East, women have traditionally worn some form of head cover due to tradition or cultural norms, not necessarily religion. Also, Catholic nuns cover their hair,’ El-Tantawy told Ahram Online.

‘My series on the veil stems from my own memory of the veil growing up in a moderate Muslim family where the majority of the women adorn a head cover. The women in my family are some of the strongest, independent and strong-willed women I know. I also wanted to show the veil as something feminine, colourful and beautiful.’

As turmoil in Egypt continues, there has been a growing increase in rebellious art work. Founder of ArtTalks Fatenn Mostafa compared the art currently being produced in the country to that of the early 20th century, when artists and writers protested British rule in their work.

‘You’re seeing that same anger and passion directed at the Muslim Brotherhood today,’ Mostafa said. ‘A lot of artists are painting nudes. I think this is a rebellion against the Brotherhood. There is also a type of self-censorship going on as some artists are trying to stay under the Brotherhood’s radar.’

Censorship is fast becoming a big problem in Egypt. A large rally took place in Cairo last month as artists, curators, critics and academics protested against President Morsi and his newly instated charter which they believe threatens their freedom of expression. Under Morsi’s regime, many artists including comedians, television presenters, editors and journalists have found themselves charged with defamation for allegedly insulting the President.

‘At the moment, there’s an emphasis on television and the movies,’ Cairo street artist Keizer told The Art Newspaper. ‘[The Muslim Brotherhood] has yet to really discover the art world, but when it does, it will clamp down. We have already had statements in the media from sheikhs saying that all art made in the past 20 to 30 years will be abolished.’

Despite the threat of censorship, Egyptian visual artists are still hard at work painting scenes from the revolution across Tahir Square, using their practice to describe their feelings about the deep division that plagues the country. Interestingly, many of these paintings have adopted a traditional Egyptian style, reminiscent of the pharonic wall paintings from 5,000 years ago but with a very current meaning.

‘The oldest paintings we know of on earth are these wall paintings…and suddenly the tradition is reborn in a way that the world can understand,’ journalist Christopher Lydon told The Takeaway.