When octogenarian Cecilia Gimenez made headlines all over the world for her disastrous restoration of the painting Ecce Homo (Behold the Man) by Spanish artist Elias Garcia Martinez, many feared the damage done to the original 19th century fresco was irreparable. In fact it is not. It appears getting the work back to its original state would be quite simple but not necessarily desirable. Probably the worst restoration in history, it has now become an extremely popular tourist attraction and a money spinner for the Santuario de Misericordia Church and surrounding district.

It hasn’t done the artist any harm either. Work by the creator of the so-called ‘Potato Jesus’ recently fetched $1400 on eBay.

Bad art can be more popular than good work. That’s the secret behind the Museum of Bad Art (MOBA) in Boston, the first museum in the world dedicated to the collection, preservation, exhibition and celebration of bad art in all its forms. One of the founders Louise Sacco says MOBA was created when the first curator Scott Wilson found this painting leaning against a rubbish bin.

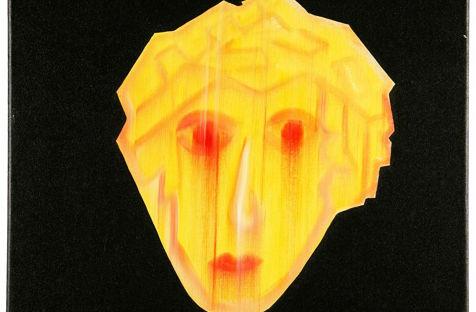

Lucy in the Sky with Flowers – Unknown

24″ x 30″, Oil on Canvas

Acquired from trash in Boston

Wilson was going to throw the painting away to sell its ‘lovely’ frame but Sacco’s brother said, ‘That is so bad it’s good. I want it.’ As it turns out, he wasn’t alone. The group put together about 30 other pieces of bad art and threw a housewarming party. In a tiny house, 50 guests quickly turned into 200.

‘People kept calling their friends and saying: ‘You’ve got to come over and see this’,’ says Sacco, who is now the permanent acting interim executive director of MOBA (yes, job titles at MOBA are as quirky as the art on show). The next day we had the conversation about how there was something there that we needed to keep doing. That was 1994. We never thought that 19 years later we’d still be in existence and would be a worldwide phenomenon,’ she says.

MOBA now has a collection of 600 works across and has been featured in Wired, Rolling Stone, The New York Times, The London Times and many other prestigious publications. ‘We’ve been on TV in Indonesia, Germany, Scandinavia… The media frenzy for the first few years just dazzled us,’ says Sacco.

As MOBA rose to fame, Sacco and her all-volunteer staff were constantly bombarded with two particular questions: Is there really such thing as bad art? Who and what exactly can determine what art is good or bad?

‘For people who say there is no such thing as a bad art, I have no patience. If there’s no such thing as bad art, there is no such thing as good art. Either we are going to make judgments about art or not, and clearly we are,’ says Sacco. ‘What we found is that our judgments at the Museum of Bad Art are just about universally accepted. We maintain that bad art is as difficult to define as is good art and what we tend to fall back on is the definition of pornography: I can’t define it, but I know it when I see it,’ says Sacco.

Velvet paintings, oil canvases of dogs playing poker and the works of Thomas Kinkade spring to mind. But MOBA isn’t interested in kitsch. The curators want art that fails as art.

‘I’m interested in things that were created in all sincerity, and not things that were created cynically, to make a commercial product,’ says MOBA curator-in-chief Michael Frank. ‘Bad art is art that was created in an attempt to make some kind of artistic statement and simply has gone wrong. Either in the execution or in the concept,’

Sacco says when people think they’re disagreeing with MOBA they are inclined to say ‘That’s not bad, I like it’. But that critique misses the point. ‘We love all of them. Bad or good is not the same thing as ‘I like it’ or ‘I don’t like it’…If a museum of fine art or a museum of modern art gets to make those judgments, then the Museum of Bad Art gets to make these judgments and you’re free to disagree with us.’

But it’s hard to disagree with MOBA when the gallery articulates its rationale for choosing a work. The collection includes works with too many layers of meaning and excessive imagery. There are portraits made by unskilled artists who have trouble painting hands and feet so leave them out or hide them. Landscapes have marching trees and lakes start and stop without reason.

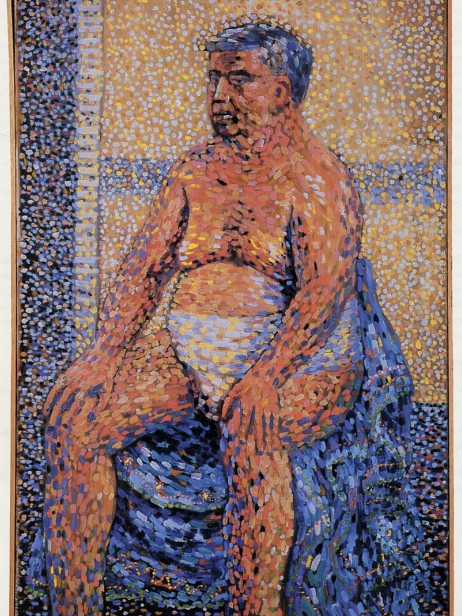

Sunday on the Pot with George – Unknown

22″ x 37″, Acrylic on Canvas

Donated by Jim Schulman

This is one of Sacco’s favourites. ‘I’m not a painter but I understand that pointillism is difficult and the person who did that was skilled at it. They were able to show detail folds in a towel, and it’s a very specific person. It’s not a generic man, this is very individual, but why would you put that much effort into a guy in his tiny whities sitting on a toilet? It’s hard to understand,’ says Sacco.

MOBA now has imitators. In 2004, Australian second-hand dealer Helen Round founded a charity museum in Melbourne titled the Museum of Particularly Bad Art (MOPBA). She was inspired by MOBA and some of the bad art she came across in op shops when travelling the US in the 90s. Round currently owns 406 works – Australia’s largest collection of bad art. ‘Quite often with bad art, it is someone’s learning process. They might become good later, or not. The person in the middle, that is the person I want to remember and celebrate,’ she says.

Round created MOPBA to protest against the Chapel Street Festival in 2004. She also established the Itchiball Prize, where the general public could submit their own bad pieces of art or found works. ‘I put up a $400 budget in response to [the festival’s] $400k budget, to see if we could get more publicity for the Chapel St precinct. It was all about having an exhibition for charity, instead of another wine, fashion and food festival. We wanted something different, we wanted to be kind to other people and animals.’ Although the museum and the prize have been out of action since 2010, Round has plans to resurrect what became a very successful initiative in the near future.

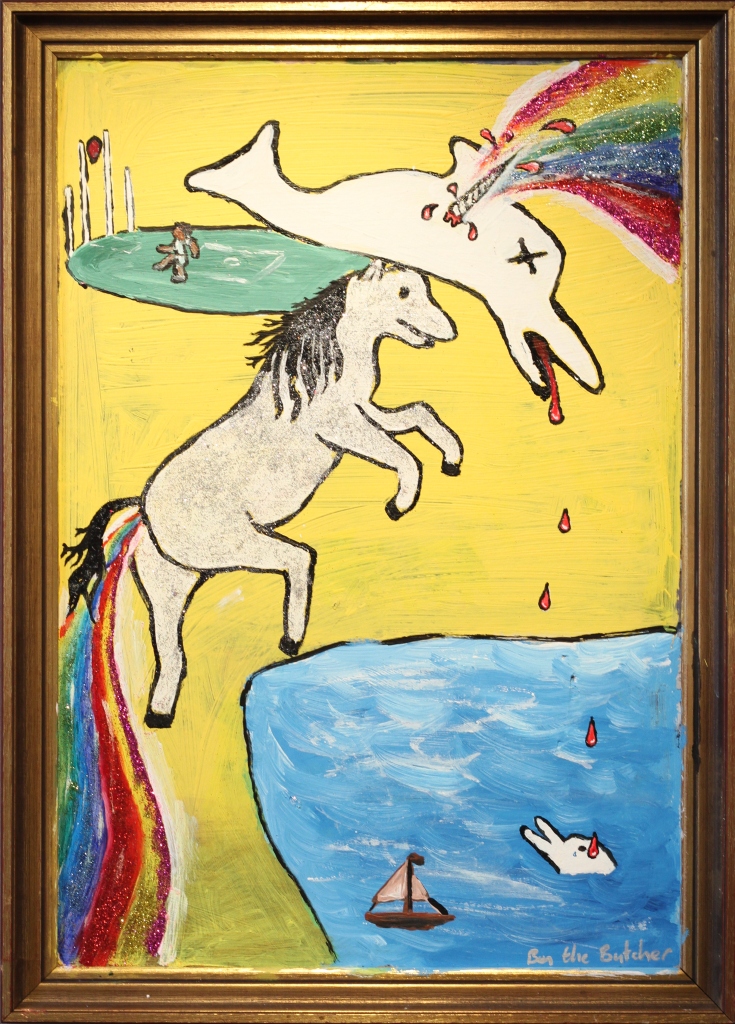

Why Do We Need A Porpoise In Life – Ben Butcher (Itchiball Prize Winner 2010)

After being awarded the last Itchiball prize in 2010, Ben Butcher became known as Australia’s worst artist. How does it feel? ‘It’s great! Oscar Wilde once said “worse than being talked about is not being talked about,”’ he says. ‘Just because it may not be seen as technically good, it doesn’t mean it’s crap. Look at Van Gogh, when he was around people thought he was crap, but he was just painting for himself. It took a while for people to catch on.’

‘Maybe my art isn’t bad. Maybe my art is awesome. People have a bit of dialogue with my art. Truly bad art is art that doesn’t have anything to offer and it’s absolutely boring. There is no story, no response or interest from the viewer. If bad art causes reaction and people hate it and want to destroy it then it’s not bad, it’s doing its job. If it’s something that sits on the wall and people just walk past, I would then say that is truly bad art,’ says Butcher.

Sydney artist and research scientist Lloyd Graham is, so far, the only Aussie artist featured in MOBA’s collection. ‘A number of other Australian pieces were offered but they never came,’ says Frank.

Graham’s painting AIM 2 – a portrait of his girlfriend – was published in the last edition of the book Museum of Bad Art: Masterworks. While The Artist As A Young Man, an ‘emotive’ self-portrait of the artist in the late 70s is also in the museum’s collection.

‘I have painted a number of abstract works that I am quite happy with. At one point I decided to give portraiture a try, and used oils to paint both a self-portrait and a picture of my partner, Lyn. I slaved over those paintings for weeks, but my comprehensive lack of training, experience and skill made for grotesque outcomes. I hid the paintings in a cupboard while the paint dried, and by the time I re-discovered them I had stumbled across the MOBA website. Reviewing my handiwork several months later through fresh eyes, I could only see them as epic failures that conformed perfectly to the spirit of MOBA,’ says Graham.

When Graham submitted AIM 2 he included the following description with the image: ‘[This is my] partner Lyn, losing the battle with the middle objective of her research grant proposal (something to do with cross-talk between insulin-like growth factor binding proteins and retinoid-X receptor heterodimerization, since you ask).’

The painting may have been a failure but the effort did generate a scientific paper and Graham jokes that ‘when my scientific work is going badly, I can draw solace from my status a published artist’.

Respecting the artists has always been a major concern of MOBA. ‘We’ll

never say negative things about the art, it is our intention to

celebrate and share these pieces and if we are making fun of anyone,

it’s art critics and art writers,’ says Sacco. ‘Artists are hard on

themselves, very often they’re not as bad as they think they are at all.

Maybe they’ve had a bad

day… But we do own a few pieces that were done by professional artists

who did have something go awry and wanted to make the best of it by

getting it to us.’

Entry to MOBA is free, and the museum is estimated to be visited by 10,000 people each year. Sacco says they enjoy the process of commenting and understanding what makes bad art but perhaps they also gain a better understanding of good art.

Says Graham, ‘My own efforts to paint faces have greatly deepened my admiration for those people who can do it properly, so – on a prosaic level – bad art can serve as a cautionary tale that highlights the skill of the gifted artist. But sometimes the mutant progeny of a flawed artistic process is not without a certain nobility. If the purpose of art is to stir the emotions, then a failed work may still do that effectively; a true painting disaster is both a comedy and a tragedy, and as such it may appeal to a far wider audience than a competent work.’