In view of Banksy’s position of distaste for the growing commercialisation of his work, it was somewhat surprising to find that he had apparently endorsed the actions of Nick Loizou, a 30 year old graphic designer and builder, and Bradley Ridge, a 31 year old restaurateur; the two friends who had physically removed one of Banksy’s outdoor public works from a site in South London at the end of last year and are now looking to sell it.

On a blog written in November it asserted “according to Mr Ridge, Banksy himself has given his blessing to the project through an intermediary, saying: ‘Well done and good luck.’” And yet are these words those of support or actually the parting words of a detached, honourable opponent to such opportunism?

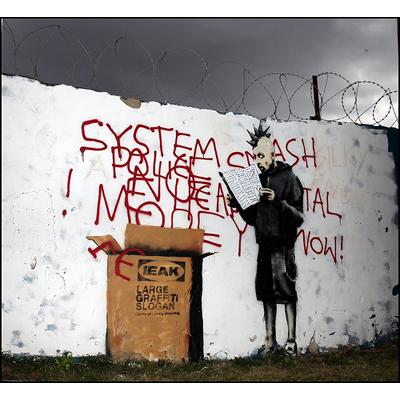

On the 9th of November 2009 Nick Loizou and Bradley Ridge heard about the Banksy piece called Large Graffiti Slogan which had appeared on a wall on an industrial estate in Croydon, South London in August 2009. The piece referenced the proximity of the Croydon Ikea store with its image of a punk reading the instructions of an Ikea “Large Graffiti Slogan” kit; from the half-opened cardboard box spray-painted letters spill on to the wall.

As the months passed, other people added to the graffiti tumbling out of the box, ugly tags but also slogans such as “Real Graffiti” that obcsured the original work of Banksy. It was for this reason, to preserve the artist’s work from “vandalism”, that Ridge and Loizou convinced the concrete company Hanson Premix to sell them the wall with the promise of conservation. They removed the wall, drove it away and restored the work to its virgin state, post-Banksy, pre-graffiti…in their own home.

The piece was announced by Loizou and Ridge, in late January, to have been valued at £500, 000 (having spent 13,000 on its purchase, excavation and restoration). Two weeks ago it was reported, however, that they face problems with authentification as, according to The Telegraph the men

“have been unable to certify the image as genuine because the artist has refused to officially recognise it as his own work. Banksy, who is known for keeping his identity a close secret, reportedly does not like the idea of other people making a profit from excavating his works from their original sites and selling them on.”

The markets of London, such as Greenwich, Camden and Portobello do a brisk business in fake Banksy canvases, T-shirts and mugs decorated with Banksy stencil designs. The ironically named “shop” option on Banksy’s own website (there are three options: “indoor”, “outdoor” and “shop”) however, is empty of merchandise except to say:

”All images are made available to download for personal amusement only, thanks. Banksy does not endorse or profit from the sale of greeting cards, mugs, tshirts, photo canvases etc. Banksy is not on Facebook, Myspace, Twitter or Gaydar. Banksy is not represented by any form of commercial art gallery.”

He recommends an organization called Pest Control as a place to register complaints about unrightful ownership or abuse of graffiti.

When Brad Pitt spent over £400.000 on one of Banksy’s studio works his career looked to echo those of Keith Haring and Basquiat in the eighties. What is the outcome of taking his works out of the public space and selling them to museums as regards meaning is a question that arises.

Banksy has represented a real political force in recent European art because he has been so careful of the financial and physical worlds with which his work has brought him into dialogue. Banksy’s relentless subversiveness, in the messages of his work, his trickiness, his continual play with destabilizing authority, his attempt to awaken awareness about environmental degradation, war, unjust power and simple stereotypical limitations are astonishing in their display of social concern and consciousness and sheer artistic design brilliance.

Banksy, like Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, Keith Haring and Blek le Rat before him, Banksy appeared to choose the street as his context specifically because he wanted the opportunity to speak to people directly and because political intent was not secondary to his work’s meaning.

All of the latter street artists, and the many, many others working today, are united in that their works are underscored by a political intention to liberate individuals from passive absorbtion of information and to actively promote dialogue; to repossess public space from the tyranny of advertising and official signage.

Jenny Holzer’s lists of Truisms which went up in poster form throughout the walls of New York 1978 were frequently graffitied by onlookers. It was viewed as a valid response, and a dynamic one, from the audience. Was the graffiti response to Banksy’s work really such an aberration or can it be viewed as a positive outcome and a valid street act?

To be casting the response of people to the Large Graffiti Slogan as “vandalism” is nonsensical in some sense, as the original work has no more rightful a place, except that Banksy is famous now. To say “response” is bad is, furthermore, political.

One of Banksy’s own strategies in the 1990’s was to actvely incite graffiti from passersbyers by stencilling an official looking sign, complete with Royal Crest, which read:

“By order National Highways Agency, this wall is a designated Graffiti Area”

Within a few weeks, the bare walls all over London on which he stenciled these signs were filled with graffiti done by others. The line between vandalism and involvement is blurred. The latter is viewed as a successful piece, must the Croydon graffiti be viewed as the mindless act of vandals or as audience response?

Banksy would have known and perhaps predicted such fecundity of the streets’ writers as that that spilled on to the Croydon piece; the image itself played on the notion of a box spilling out with messy writing.

The nature of street art is that it can elicit a direct response from the audience because it is in, a sense, existing in a space to which everyone has equal rights. In this sense language or messages in the public space can be viewed as communication through language rather than subjugation through language, which occurs when there is no possibility of response.

In his book Banksy writes explicitly about the public’s right to write in public:

“The people who truly deface our neighbourhoods are the companies that scrawl giant slogans across buildings and buses, trying to make us feel inadequate unless we buy their stuff.”

At the end of his book he gives advice on how to spray stencils with paints, how to avoid the police and says cheerfully, “Mindless vandalism can take a bit of thought”.

When Bradley Ridge and Nick Loizou say that they have acquired the Banksy work because they “really want to sell it to a gallery or a museum so the maximum number of people can enjoy it”, there is an awareness that it is a money-making exercise.

It is the commercial value of Banky’s work that underpins his promotion to status of “artist”, and it is surely a status he must balk at if it means that other graffiti writers are demoted to vandals without further thought to the meaning of street art as public space.

The response to the Ridge/Loizou action reveals that after 20 years, Banksy has been largely assimilated as a national UK treasure. It also reveals however, that the unthinking notion of graffiti as vandalism persists despite the far more pernicious culture of advertising that dominates public space in the UK, with its images promoting the social goals of physical vanity, individualism and soulless consumerism. What is new is that some graffiti makers have been promoted to “artists” by the art world.

Banksy’s work reveals wonderful artistic ability. However the pertinence of his work, like many subversive artists, lies in its context and its position outside the connoisseur markets. This is changing and Banksy is wise to remain incognito to maximize his freedom from assimilation as far as possible.

As many French postmodernists, and Noam Chomsky, have warned, late Capitalism will only too readily absorbs voices of opposition by giving them airtime, to disarm and pre-empt meaningful or unmonitored stirrings in the consciousness of society and to perpetuate the “illusion of democracy”.

The first way this is done is the art market and investors buying the art of the streets (not the studios) and moving it into the galleries; the safer context for wayward thinking, for the attention of the few and with no opportunity for audience participation; a clean, quiet space where passivity reigns. The streets are quite a different story. May Banksy remain there.

.