Theatrical extravaganzas such as Afrika Afrika, The Lion King and the famous South African production, Umoja, have injected London with the heat and exoticism of the African continent. Exploration of everything African is now penetrating cosmopolitan London, creating a home from home experience on stage for those living within the diaspora and for those who want to learn more. With such rich and exciting traditions, it is fantastic to see Britain welcoming and taking an interest in the free-spirited African culture – to witness years of versatile history depicted on large stages in celebration of all that is African.

This genre of theatre has not only provided entertainment but has also managed to dissolve perceptions of Africa as esoteric and a cultural vacuum. No longer is this culture depicted in a manner perceived to sit more comfortably with Western audience members’ expectations of all that is African. African theatre productions like The Dilemma of a Ghost by Ghanaian playwright, Ama Ata Aidoo, and South African play Sizwe Banzi is Dead are indeed presenting the truth, and considering the vastness of the African culture, this is being done effectively. Director and actor Peter Mutanda from TUF Productions, a Zimbabwean theatre company based in Leeds, appreciates this explosion of African theatre, and is glad that TUF are now joining this troop. “We are bringing fresh air to British audiences. For centuries, British theatre has predominantly centred on explorations of contemporary theatre, but lately a new type of art form is being created, with dance and story telling. As a theatre group we are trying to combine mainstream contemporary theatre with African music and dance.” Directors and writers are now choosing to portray aspects of this culture by delving into relationship issues, the way in which traditions within families differ from Western values, history, song, dance and much more. These explorations thus create a platform for a renewal of people’s social values and identity and show Africa as a continent rich in culture.

Following in the footsteps of the vast number of South African and smaller West African groups, TUF Productions – which stands for Theatre Under Fire – is a theatre group who are transferring experiences as natives of Zimbabwe and using theatre to communicate a message of hope and truth. TUF began in August 2006 with their first official show, Cry My Zimbabwe, which dramatised the atrocities of President Mugabe’s horrific regime in Zimbabwe and explored the reality of political asylum seekers living in England. Their second and most recent play, titled The Twilight Rainbow, was a colourful mixture of red-hot African beats, singing, acting and dancing, with a powerful storyline of adversity and cultural identification. Peter states that “Our theatre aims to give a very positive depiction of African culture” it is Africans telling their own stories rather than someone else trying to do so, because they may never portray them correctly. Whenever African culture or history has tried to be portrayed by Western directors, there are always queries. Look at the films Blood Diamond and Hotel Rwanda” in my opinion they were portrayed incorrectly and only really satisfied particular audiences. So, in our theatre we want to tell the truth and positively portray ourselves. Sometimes it may be negative, but we are generally portraying a true picture”.

The question of true representation on stage is one often expressed by some Afro-Caribbeans and Africans living within the diaspora. These audience members often wonder whether shows such as Twilight Rainbow and various others put on by African theatre companies such as Talawa Theatre, are indeed true representations of African culture – depictions which could be used to educate this generation of both black youth and other nationalities who may only get to witness the African continent through the lenses of BBC One News. For Peter of TUF Productions, the answer is yes – these shows will educate their audiences because “all of the actors in our company have experienced the pain in Zimbabwe and this is what makes their performances so unique and sincere. Some of the members of TUF Productions have been tortured, arrested, or persecuted just for being a protesting artist and one of the actors was actually telling his own story on stage – he was beaten, tortured, electrocuted and terribly treated”.

But what of shows like The Lion King and, as the November 2008 issue of Ebony magazine put it, “the colour-blind casting of The Little Mermaid”? Both are productions that cannot be disregarded for their phenomenonal theatrical quality, yet could cause some people to question whether they indeed afford black culture a sufficiently wide lens to be viewed through? If the answer is no, should they have to simply because the cast is predominantly made up of black actors?

The response of Samiat Pedro, an arts journalist and writer, maintains that more mainstream shows such as The Lion King do indeed establish a window for black culture to be viewed through, because the show “demonstrates one important aspect of African culture: music – specifically traditional South African music. However, just because these shows explore some aspects of Africa, [it] does not mean that a production such as The Lion King should be labeled as a complete guide to African culture (which in itself is complex.)”.

As explained by Sophia Jackson, the Editor and founder of Afridiziak Theatre News, a website celebrating Afro-Caribbean theatre, what these shows do is to “help audiences to appreciate the contribution that African and Caribbean culture makes to society and the world at large. [They] also give black actors more opportunities to use their craft. If audiences want to be educated, however, they stand a better chance of gaining knowledge of African and Caribbean history and culture from less mainstream productions and in smaller theatres, including plays put on by Talawa and Eclipse. Ideally, if these smaller productions were performed in the West End this would enable more people to see them”. One view common to both women is that African shows should be celebrated in all their dexterity and as a craft because, as Samiat says, “it is great to see so much detail and skill on stage”.

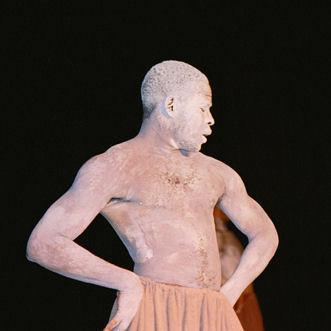

The emergence of performances centred on black culture should be applauded for the ability to establish a new and original theatrical style – a blend of musical exploration and commentary. The interactive pieces bend the rules of traditional theatre where people just sit and watch, and instead invite the audience to comment and question. Dance shows such as Heart Of Darkness, choreographed and composed by Bawren Tavaziva, explores particular topics of importance within the black community through four short dance pieces – Silent Steps, Kenyan Athlete, Sinful intimacies – which is a sensual duet exploring African unease with same-sex love – and My Friend Robert, a piece drawing on Bawren’s personal experience to ask how “an inspirational African leader, adored by his people, can descend into horror, corruption, violence, disease and economic meltdown”.

More Afro-Caribbean theatrical productions Britain could help augment pride in and appreciation for other cultures. Luckily for many who live in London in particular, developing more cultural awareness is very achievable because the city is open to new and colourful productions that help dispel old myths of ethnicity and celebrate it instead.

For more information about TUF Productions visit www.tufproductions.com

Information on Heart Of Darkness visit www.tavazivadance.com

Information on Afridiziak Theatre News visit www.afridiziak.com/theatrenews